Published on May 20, 2021 by Yuxi Wang

On 10 November 2020, Shanghai Clearing House announced that Yongcheng Coal & Electricity Holding Group Co., Ltd (Yongmei Holding, or Yongmei) was unable to make the RMB1bn payment of principal and interest on its super and short-term commercial paper (SCP) on time, marking another state-owned enterprise (SOE) default. It was not the first government-affiliated entity to default in the past two years. The market was, however, stunned, as investors felt they were viciously treated this time around due to a series of government-approved transactions just prior to the actual default. Through these transactions, the company had transferred a considerable number of valuable and important separable assets with zero consideration to other SOEs controlled by local governments. This action dealt a heavy blow to the confidence of fixed-income investors in China’s domestic bond market, as the market suspected it may signify local-government tolerance of SOE debt default.

Yongmei was rated “AAA” by China’s domestic rating agency, largely due to the credit endorsement it benefitted from due to its SOE background. The default of such an SOE provided us with a reason to re-think our credit assessment framework of government-related entities.

Look beyond the scorecard

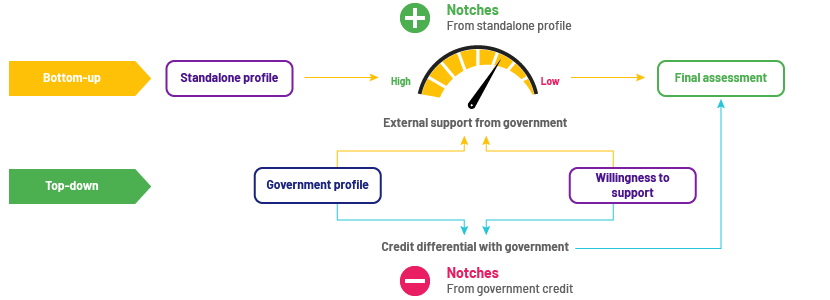

Rating agencies utilise either a bottom-up (standalone plus external support) or top-down (derived directly from government capability) approach to assess government-related issuers’ credit quality, aiming to deliver a stable and comparable ranking of those entities. It is, however, generally difficult to provide early warning of a pending default or an acute worsening of creditworthiness until a credit event occurs or just before it occurs.

Source: Acuity Knowledge Partners

It is still logically correct to assess credit quality by considering the company itself and any external resources, since the possibility of default by a bond issuer is conditional: it depends on the standalone default possibility and the probability of receiving support from a viable third party.

As the factors that drive the standalone credit profile and determine the availability of external help keep changing, investors should look at each component of the framework only in a dynamic sense and not statically. For example, when assessing a standalone credit profile, rating agencies usually use a pre-set scorecard or mapping card with a pre-determined weight for each factor to derive an assessment that may not always be adaptable, as credit fundamentals of a company change. When a company defaults, liquidity and refinancing problems could take most of the blame, and at that point, operating data is seldom cited as the reason.

That said, the readily available assessment under the current framework still provides a good reference point, as it at least helps the market identify weaker names in operation and financials, so that investors can further trace the evolution of the liquidity condition and the health of financing channels.

The other critical point deserving attention in this instance of default is how we should look at the relationship between a company and its parent, especially when the parent is a powerful government entity. Under the current framework, the expected level of extraordinary support was derived from the supporting entity’s capacity to help and its willingness to do so. While supporting capacity is generally reflected by the government’s own credit position (here we assume it as a given factor), the discussion will focus on the willingness – a function of the link between the debt issuer and the supporting entity, and the importance of the issuer to the supporting party.

Is it always good to have a strong relationship with a powerful parent?

A typical factor in assessing the link is the parent’s shareholding in a company. An absolute controlling status usually suggests a strong relationship between parent and subsidiaries, and to avoid the paring in equity value, equity holders have the incentive to bail out its subsidiaries, benefitting the credit standing of the issuer. However, such support is likely extended only when the controlling party plays by the rules.

The basic assumption of credit analysis is that debt holders should be paid before equity holders and assets can be disposed of, when necessary, to repay debt. Based on this, an analysis of asset value is important, where debt holders can project their recovery of investment based on an investee’s asset value and their respective ranking in the capital structure.

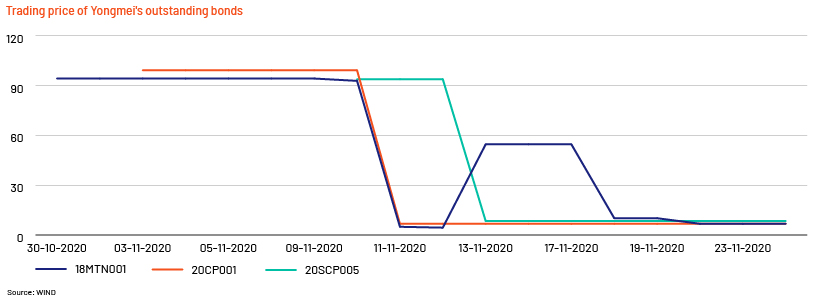

However, in the context of a government-owned entity defaulting in a market lacking liquidation practices, such as China’s domestic bond market, debt holders are the disadvantaged group, with their power and methods to claim their investment interests crippled by the strong link between the SOE and the controlling government, in some cases. In Yongmei’s case, with the highly liquid listed equity investments, whose market value was sufficient to repay the defaulting principal (but not large enough to breach the covenant), transferred out on approval by the controlling government, bond holders perceived liquidation of other operating assets as an option off the table, making the market-implied recovery rate of bonds issued by Yongmei dip below 10%, as suggested by the RMB6-9 trading quote of 100 par after the default event.

Yongmei’s failure reminds the market of the default by Qinghai Salt Lake Industry Co., Ltd in 2019. Qinghai Salt Lake’s asset value was more than sufficient to repay all debt outstanding, but the Qinghai SASAC, the controller of the defaulting company, guided Qinghai Salt Lake to restructure and made the bond investors incur a loss, while avoiding an equity wipe-out. In such cases, the government’s equity stake did not act as a cushion for bond investors; thus, the benefit of a strong link with the government owner could be capped if the market mechanism, legislation, or corporate governance could not provide enough protection to bond holders.

Why should they pay to help?

Another factor in assessing “willingness” is a company’s importance to its parent, which is subjective and will only become more complicated when the parent is a government whose political target and mindset are changing. The current analysis framework determines the importance of an SOE to the government through the company’s role and duties undertaken. Typical SOEs likely to receive government support are those with unique political status, possessing strategic resources/assets and providing essential public services, or those important for the proper functioning of a specific sector. That said, it is not reasonable to equate an SOE’s functional importance (i.e., its importance in maintaining an operation) with its credit importance (i.e., the importance of avoiding default) to the controlling government. A government would help maintain an SOE’s creditworthiness only in the context that a default by the SOE would hold it back from honouring its function, but when the debt holder lacks the power to access or dispose of the functional assets of an SOE, government incentive to provide support only weakens.

Usually, the assessment of an SOE’s importance comes from the SOE’s role, but it may also be important to look at it from the other side, i.e., from the government’s perspective. The local government, as an entity, plays many roles:

(1) A layer in the administrative structure, where it operates under political guidance/demand from the central or upper-level governments;

(2) The shareholder in SOEs, where it also tries to maximise its benefit given the heavy financial pressure it usually bears; and

(3) Government officials as individuals and the actual decision makers, with their own concerns and personal judgment.

A government’s choice would, therefore, be governed by the role it plays. For example, in areas with ongoing infrastructure requirements, a default would ruin the financing conditions for local-government financing vehicles (LGFVs), making it very difficult for the government to meet its political targets and translating into consequences for the responsible officials. The government would, therefore, employ all means at its disposal to ensure the credibility of associated LGFVs. But in areas where there is limited ongoing capital outlay and the outstanding LGFV debts become a pure burden, the incentive of the government helping to honour that debt seems to be much less, unless other political pressure is in place. Also, if a functional or profit-seeking SOE faces financial distress, but the debt holder lacks access to the core assets under a certain institutional framework, that is, the state-owned strategic assets remain within the regime, it will be costless (sometimes even beneficial) for the government to allow the SOE to default or restructure. With more and more SOE-related credit events in recent years, the standards for assessing an SOE’s importance should also be calibrated, as breaking the rigid redemption of instruments issued by SOEs has become the new policy trend.

All focus on LGFVs

Following Yongmei’s default, the common assumption that commercially oriented SOEs could receive much less government support seems to hold, but investors are also now looking at LGFVs – those special SOEs undertaking government projects. Although the market has seen LGFVs defaulting on non-standard debt instruments, none of the debt securities issued in the open market have actually gone bust. Even if they missed the payment date, “legitimate” LGFVs (as perceived by investors) always pay their debts. However, with LGFV credit events progressing from default on non-standard debt instruments to “technical default” on LGFV private placements (unlike the concept perceived in the global capital market, in China’s bond market, this means missing the payment date due to technical reasons), the market feels the government is trying the bottom lines of investors. It is now very close to breaking the rigid redemption pattern that gave bond investors the opportunity to buy bonds ignoring the underlying credit quality of LGFVs and led to the strong belief in LGFVs, but the government is yet to make the decision.

The weak standalone and strong parental support structure created many investment-grade names in the market, and investors were concerned that once-strong bonds were getting weaker. While the parent’s intent is hard to fathom, it is probably a good time to abandon the “belief in SOEs” and “belief in LGFVs” and return to fundamental analysis.

How Acuity Knowledge Partners can help protect foreign investors from credit shocks

With Chinese names becoming the dominant force in the offshore bond market, the market has seen a large number of offshore bond issuances from China SOEs. The increasing overlap in issuer exposure formed a strong link between offshore and onshore markets, and we believe it will be wise for investors in the offshore market to be prepared for any spillover effect from credit trends in China’s domestic market.

Acuity Knowledge Partners, with a delivery centre in Beijing, has a profound understanding of China’s local market. Equipped with full knowledge of credit research, we are able to provide our clients with credit support across the spectrum, including in-depth company research, financial model building, company and group capital structure analysis, and indicative rating analysis that provide unparalleled insight on China-based issuers and enable real-time tracking of portfolio coverage.

Sources:

S&P Global Ratings – https://disclosure.spglobal.com/ratings/en/regulatory/article/-/view/type/HTML/id/2633022

Moody’s – https://www.moodys.com/researchdocumentcontentpage.aspx?docid=PBC_1186207

Fitch Ratings – https://www.fitchratings.com/research/international-public-finance/government-related-entities-rating-criteria-30-09-2020

China Chengxin International Credit Rating – https://www.ccxi.com.cn/cn/Init/baseFile/1053/622

What's your view?

About the Author

Yuxi Wang has over 6 years of experience in credit research. At Acuity Knowledge Partners, he is part of Credit Research team in the Investment Research Division. Yuxi has worked for leading buy side and sell side institutions covering a wide range of sectors. Yuxi holds a master degree in Financial from Case Western Reserve University.

Like the way we think?

Next time we post something new, we'll send it to your inbox